Prehistorically,

rock art was the most common form of art, and it was similar in fashion to

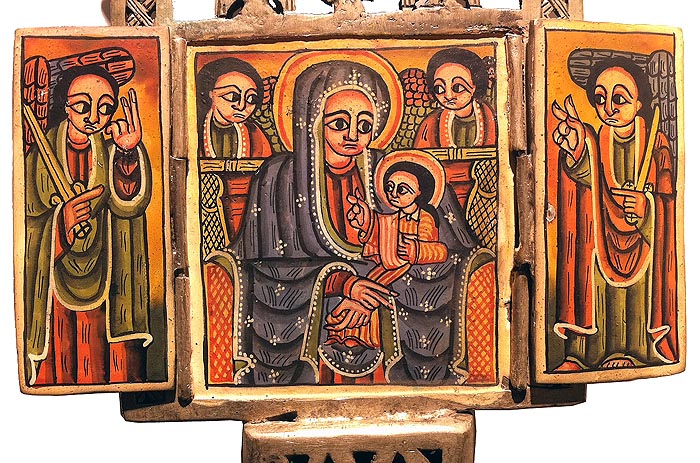

other specimens from other regions in this part of the world. After Christianity was adopted, much of

the artwork was religious-themed.

Iconography was common, characterizing the figures with their bright

colors and almond-shaped eyes.

Diptychs (panel paintings with two panels) and triptychs (panel

paintings with three panels) were also common. The churches and cathedrals themselves were fully painted in

the European tradition. There were

some minor differences; for example, angels were often depicted as being heads

with wings.

Crosses

were very important as well. Many

of these are highly elaborate and ornate.

These crosses were mostly constructed from brass and plated with either

gold or silver. Crosses used in

processions could be quite large in size and quite heavy. Smaller crosses used as jewelry were

also made and worn. Other

metalwork, such as crowns, was made for both royalty and high clergy

members.

Textile

art was also commonly produced in Ethiopia. A type of lightweight, opaque pattern-less cloth similar to

chiffon was used to drape onto religious icons. Generally, traditional cloth designs have geometric patterns

to them (although many are plain) and tend to be quite colorful.

Basket

making is quite common, especially in the rural areas of Ethiopia. Depending on its use, whether for storing

food, doubling as tables, or being used as bowls, baskets can range from small

to quite large. Designs are woven into the baskets as well.

Early

Ethiopian literature was written in the Ge’ez language. The Bible and other

religious writings dominated the early literature canon. The Ethiopian Orthodox

Tewahedo Church still uses the Ge’ez language as the language of religious

literature. The Ethiopian Jewish

community (also known as Beta Israel) still uses the Ge’ez language today as

well. The Garima Gospels are the oldest Ge’ez scripts, found in Eritrea and

thought to date somewhere between 390-660.

By

the time the 14th century came, the language of literature was

starting to shift towards using Amharic, Tigrinya, and Tigre, depending on the

location. Histories, hagiographies, and letters have been found that have been

dated during these early years through the 16th century. Works such

as “Book of Axum” and “Book of Enoch” are two famous works written in Ge’ez.

|

| Book of Enoch |

Literature

written in Amharic covers more works in the most recent centuries. Although it

also includes religious materials, it also includes educational materials,

government records, novels, poetry, and basically anything that is read

today. Because of their

multi-lingual society, the government declared the Amharic as the official

working language of the federal government. It’s also the language of primary education. Other regional languages may be used

locally and for unofficial business.

Up

next: music and dance