Handicrafts and textiles are some of the main forms of art in Tajik culture. And they really like bright colors, which are worked into their embroidery, weaving, and applique work. Hawks are an important symbol in their culture, so sometimes this is incorporated into their art, especially in their singing, dancing, and folktales.

Pottery is also a common art form, stemming from the Samanid period. They developed a type of painting called slip painting, where they would add colors into semifluid clay and then brush on a glaze on top to keep the colors from running when it’s fired. A lot of pieces (mainly bowls and plates) had animals or Arabic calligraphy on it. Bronzecasting and other types of metalwork were also pretty commonly done during that time as well. A lot of these art styles were spread throughout the region.

|

| Read more about this painting here. |

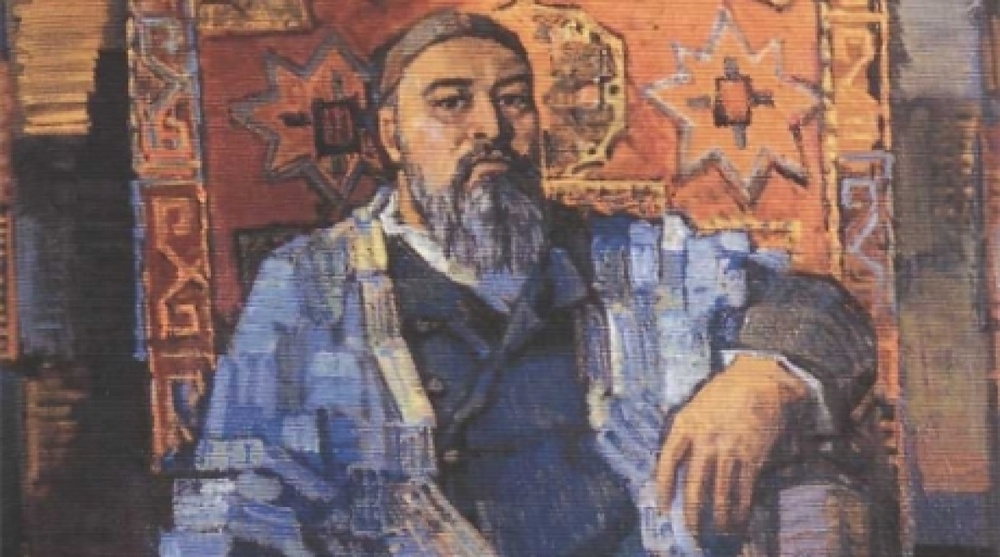

Arts during the Soviet years were under scrutiny due to the sociopolitical atmosphere at the time. While many Tajik intellectuals were using their arts as a means for their anti-communist sentiment, the Soviets were painting them as backwoods and primitive to a degree. However, the Russians actually did a lot for expanding arts like cinema and fine arts, especially in the beginning. In fact, one of the main influences the Russians had was introducing Western-style painting to Tajik artists.

For many Tajiks, there is not much difference between their culture and Persian culture. In their eyes, they are pretty much the same. And because the Persian Empire included not only Tajikistan but also neighboring Uzbekistan, several of what they consider their cultural centers (mainly Samarkand and Bukhara) are actually now located in Uzbekistan. But I guess it’s how like areas of Texas (or pretty much most of that corner of the country) used to be part of Mexico.

|

| From the movie Silence (1998) |

With the standardization of the Tajik language, it gave credence to Tajik literature, a platform for which it to grow. As much as their indifference and distaste for the Russians, Tajik literature did begin to grow during the late 1800s. The main style many Tajik writers embraced was socialist realism. Poetry is a common writing style as well as plays. Tajikistan also had a fairly successful film industry at one time. With its beginnings in the 1930s, some film buffs consider the 1970s to be the Golden Age of Tajik films.

Some of the authors who have had an influence on Tajik literature include Sadriddin Aini (poet, writer, educator), Abu’l-Qasem Lahuti (Iranian-Tajik lyrical and socialist realist poet), Mirzo Tursunzoda (poet who wrote about social change and collected oral literature), Satim Ulugzade (Soviet-Tajik writer, playwright, translator), Karim Hakim (Tajik Soviet novelist, short story writer, playwright), Pairov Sulaimoni (poet, writer), Roziya Ozod (female poet, writer, teacher), and Aminjan Shokuhi (poet).

Up next: music and dance

.jpg)