The music of Tajikistan is fairly similar to the styles of other Central Asian countries, namely Uzbekistan. They even share many common genres and instruments. Their classical and folk music spans not only different areas of Tajikistan but can be a bit more regionalized.

One particular genre shared between Tajikistan and Uzbekistan is shashmaqam. The name literally means “six modes.” The lyrics generally come from Sufi poems about divine love. Historically, it’s thought that shashmaqam originated in the cultural city of Bukhara and was performed as court music. Stalin saw this as representing the feudal ruling class and was ok with it. It’s made some changes over the years, but it’s still thought of highly as a traditional musical genre.

Another type of music heard is performed throughout the Pamir Mountains regions (and more specifically the Badakhshan areas of Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Pakistan) is falak. Also having lyrics based on Sufi poems, it’s not just limited to songs about divine love, but also draws upon themes of separation and reunion as well as human love and suffering.

Unlike other countries, Tajik national songs are almost always performed in a single voice. Music is often performed for ceremonies and festivals, and genres can vary. Tajik music utilizes many of the same instruments that are heard in much of this region. String instruments are quite common: rhubab, tanbur, dutor, violin, and the gidzhak are often heard in their music. They also use quite a few percussion instruments like the tablak (a type of clay kettle drum), kairok (castanets made of stone), and the doira (similar to a tambourine). They utilize a variety of wind instruments as well: surnai, nai, and karnai. Today, they use many modern day Western instruments along with the traditional ones.

Traditional dances incorporate more than just dance. It uses elements of pantomime, drama, and circus styles to tell a story. They will have great performances that take over the entire stage. Generally, dances are divided up between pantomime dances (based on animals and birds), ceremonial dances (like the rakskhoi marosimi, or dance beside the death bed), and ritual dances (like the boft [weaving] or the oshpaz [the cook]). And then there are men’s and women’s versions of dances.

I did manage to find a few Tajik musicians on Spotify. Several who I listened to may have been listed as pop and rock musicians, but it doesn’t sound the same to Western ears. I listened to Tahmina Niyazova, who has a soft rock feel with a Middle Eastern sound behind it. You can certainly hear the ties to Persian culture. I feel like I would be listening to this sitting in a Persian or pan-Middle Eastern restaurant.

When I was listening to Shabnam Suraya, it seemed quite upbeat, dance music for sure. In fact, this really sounds like belly dancing music. I bet you she was doing moves in the studio when she was recording it. You know she was. I only had to watch two videos on YouTube to know she dances.

I also listened to Oleg Fesov. His music uses the same traditional rhythms and instrumentation, even though some of his songs have more of a Western structure to them. In a similar style, I found an album by Shams and Muboraksho Mirzoshoev. I think they’re both the type of albums you can play if you need to relax and chill or are just melancholy.

Some bands subtly incorporate some rock elements into their music, but it still has a strong sense of Persian style. Two bands/musicians I feel fall into this category are Parem and Daler Nazarov. In some cases, they use very traditional styles in the midst of Western style; in other instances, they use traditional instruments to play Western rock riffs. So, points for originality. I do like a good mashup of genres.

Up next: the food

A blog inspired to teach my children about other countries and cultures through their food. It also includes music, arts, and literature from those countries as well.

Saturday, February 8, 2020

Wednesday, February 5, 2020

TAJIKISTAN: ART AND LITERATURE

Tajiks are very proud of their cultural history, and it’s very much tied to quite a bit of Persian history as well. In fact, many like to make the point that several of the great “Persian” artists and poets were actually Tajiks like themselves. Tajik culture is a mix of Persian, Mongolian, Arab, Islamic, and Russian influences.

Handicrafts and textiles are some of the main forms of art in Tajik culture. And they really like bright colors, which are worked into their embroidery, weaving, and applique work. Hawks are an important symbol in their culture, so sometimes this is incorporated into their art, especially in their singing, dancing, and folktales.

Pottery is also a common art form, stemming from the Samanid period. They developed a type of painting called slip painting, where they would add colors into semifluid clay and then brush on a glaze on top to keep the colors from running when it’s fired. A lot of pieces (mainly bowls and plates) had animals or Arabic calligraphy on it. Bronzecasting and other types of metalwork were also pretty commonly done during that time as well. A lot of these art styles were spread throughout the region.

Arts during the Soviet years were under scrutiny due to the sociopolitical atmosphere at the time. While many Tajik intellectuals were using their arts as a means for their anti-communist sentiment, the Soviets were painting them as backwoods and primitive to a degree. However, the Russians actually did a lot for expanding arts like cinema and fine arts, especially in the beginning. In fact, one of the main influences the Russians had was introducing Western-style painting to Tajik artists.

For many Tajiks, there is not much difference between their culture and Persian culture. In their eyes, they are pretty much the same. And because the Persian Empire included not only Tajikistan but also neighboring Uzbekistan, several of what they consider their cultural centers (mainly Samarkand and Bukhara) are actually now located in Uzbekistan. But I guess it’s how like areas of Texas (or pretty much most of that corner of the country) used to be part of Mexico.

With the standardization of the Tajik language, it gave credence to Tajik literature, a platform for which it to grow. As much as their indifference and distaste for the Russians, Tajik literature did begin to grow during the late 1800s. The main style many Tajik writers embraced was socialist realism. Poetry is a common writing style as well as plays. Tajikistan also had a fairly successful film industry at one time. With its beginnings in the 1930s, some film buffs consider the 1970s to be the Golden Age of Tajik films.

Some of the authors who have had an influence on Tajik literature include Sadriddin Aini (poet, writer, educator), Abu’l-Qasem Lahuti (Iranian-Tajik lyrical and socialist realist poet), Mirzo Tursunzoda (poet who wrote about social change and collected oral literature), Satim Ulugzade (Soviet-Tajik writer, playwright, translator), Karim Hakim (Tajik Soviet novelist, short story writer, playwright), Pairov Sulaimoni (poet, writer), Roziya Ozod (female poet, writer, teacher), and Aminjan Shokuhi (poet).

Up next: music and dance

Handicrafts and textiles are some of the main forms of art in Tajik culture. And they really like bright colors, which are worked into their embroidery, weaving, and applique work. Hawks are an important symbol in their culture, so sometimes this is incorporated into their art, especially in their singing, dancing, and folktales.

Pottery is also a common art form, stemming from the Samanid period. They developed a type of painting called slip painting, where they would add colors into semifluid clay and then brush on a glaze on top to keep the colors from running when it’s fired. A lot of pieces (mainly bowls and plates) had animals or Arabic calligraphy on it. Bronzecasting and other types of metalwork were also pretty commonly done during that time as well. A lot of these art styles were spread throughout the region.

|

| Read more about this painting here. |

Arts during the Soviet years were under scrutiny due to the sociopolitical atmosphere at the time. While many Tajik intellectuals were using their arts as a means for their anti-communist sentiment, the Soviets were painting them as backwoods and primitive to a degree. However, the Russians actually did a lot for expanding arts like cinema and fine arts, especially in the beginning. In fact, one of the main influences the Russians had was introducing Western-style painting to Tajik artists.

For many Tajiks, there is not much difference between their culture and Persian culture. In their eyes, they are pretty much the same. And because the Persian Empire included not only Tajikistan but also neighboring Uzbekistan, several of what they consider their cultural centers (mainly Samarkand and Bukhara) are actually now located in Uzbekistan. But I guess it’s how like areas of Texas (or pretty much most of that corner of the country) used to be part of Mexico.

|

| From the movie Silence (1998) |

With the standardization of the Tajik language, it gave credence to Tajik literature, a platform for which it to grow. As much as their indifference and distaste for the Russians, Tajik literature did begin to grow during the late 1800s. The main style many Tajik writers embraced was socialist realism. Poetry is a common writing style as well as plays. Tajikistan also had a fairly successful film industry at one time. With its beginnings in the 1930s, some film buffs consider the 1970s to be the Golden Age of Tajik films.

Some of the authors who have had an influence on Tajik literature include Sadriddin Aini (poet, writer, educator), Abu’l-Qasem Lahuti (Iranian-Tajik lyrical and socialist realist poet), Mirzo Tursunzoda (poet who wrote about social change and collected oral literature), Satim Ulugzade (Soviet-Tajik writer, playwright, translator), Karim Hakim (Tajik Soviet novelist, short story writer, playwright), Pairov Sulaimoni (poet, writer), Roziya Ozod (female poet, writer, teacher), and Aminjan Shokuhi (poet).

Up next: music and dance

Saturday, February 1, 2020

TAJIKISTAN: THE LAND AND THE PEOPLE

Tucked in the corner of the grey areas of the map where its name may not be familiar to some, is a country surrounded by a snow-covered mountain backdrop. It’s a hidden gem for those who want to avoid the touristy areas and embrace the outdoors. It’s a place for those who are looking to get away from their Western lifestyles into something different.

The name Tajikistan literally means “land of the Tajiks.” But where the term Tajik came from is up for debate. The main dispute is whether the original people were of Turkish or Iranian descent. Because of the Russian influence in its history, you may also see the name of this country written as Tadjikistan.

Tajikistan is one of the former Russian countries of Central Asia. This landlocked area is surrounded by Kyrgyzstan to the north, China to the east, Afghanistan to the south, and Uzbekistan to the west. The Tajik people are native to this area but they also lived in areas of Afghanistan and Uzbekistan as well. This country is highly mountainous: located in the Pamir Mountains, more than half the country is above 9800 ft above sea level. These mountains also give way to the Amu Darya and the Panj Rivers and over 900 lakes (Calm down, Minnesota. Your 10,000 lakes are still cool).

People have lived in these lands for a very long time. It was once part of the Archaemenid Empire and later was conquered by Alexander the Great. The Silk Road passed right through this area, and the northern parts did quite a bit of trade with China. It used to be quite religiously diverse, but once the Arabs moved into the area, it soon became an Islamic state. It changed hands so many times, from being under Persian rule to falling under Genghis Khan’s Mongol invasion to eventually, the Russians. During the late 1800s, Russia slowly moved into Central Asia with their Imperial interests at hand. The Tajiks really weren’t all that excited about the Russians being there, and there were conflicts over it. During the times following the Russian Revolution in 1917, Bolshevik forces burned down any building associated with organized religion. Much of the Tajik areas were part of Uzbekistan before breaking off to be its own republic in 1929. It was known as Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic, and their soldiers were conscripted into the Russian army during WWII. They remained under Russian control until the breakup of Russia in 1991; Tajikistan finally gained its independence. They fell into a civil war right away following their independence. A ceasefire was reached in 1997, and although they’ve held functional elections since then, it wasn’t without tension. Between tensions in their own country and the nearby war in Afghanistan, there have been troops of various nationalities stationed in the capital and other areas of the country.

Because of the civil war, Tajikistan’s economy has struggled. And struggle is probably an understatement to a degree. A little less than half of its GDP comes from remittances sent back from people who’ve moved to other countries for work (mainly to Russia). They also receive assistance from other countries, especially since droughts and other factors have led to a high number of people living with food insecurity. After the civil war ended, some industry has grown, especially in energy and utilities. Unfortunately, money from drug trafficking is a constant problem in this area.

The capital city of Dushanbe is located in the southwest corner of the country. It literally means “Monday,” named after a village that used to have a large bazaar held on Mondays. It sounds weird, but then again, we have stores named Tuesday Morning and Weekends Only. During the Communist years under Russia, it was renamed Stalinabad, after Joseph Stalin. (...See, we knew Stalin was bad. They practically spelled it out.) They generally have a Mediterranean climate since the mountains keep back a lot of the colder Siberian air. Today, it has several universities, sporting venues, shopping centers, arts centers, and museums. Dushanbe also boasts the second tallest freestanding flagpole in the world. At 541 feet, it’s only 14 feet shorter than the Washington Monument. (It’s only second to the one in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, coming in at 561 feet.)

Although technically Tajikistan is a secular country, about 96-98% of the people here are Muslim. And more specifically, they follow the Hanafi school so Sunni Islam. You’ll also find small populations of Christians (mostly Russian Orthodoxy and various Protestants), Buddhists, and Zoroastrians.

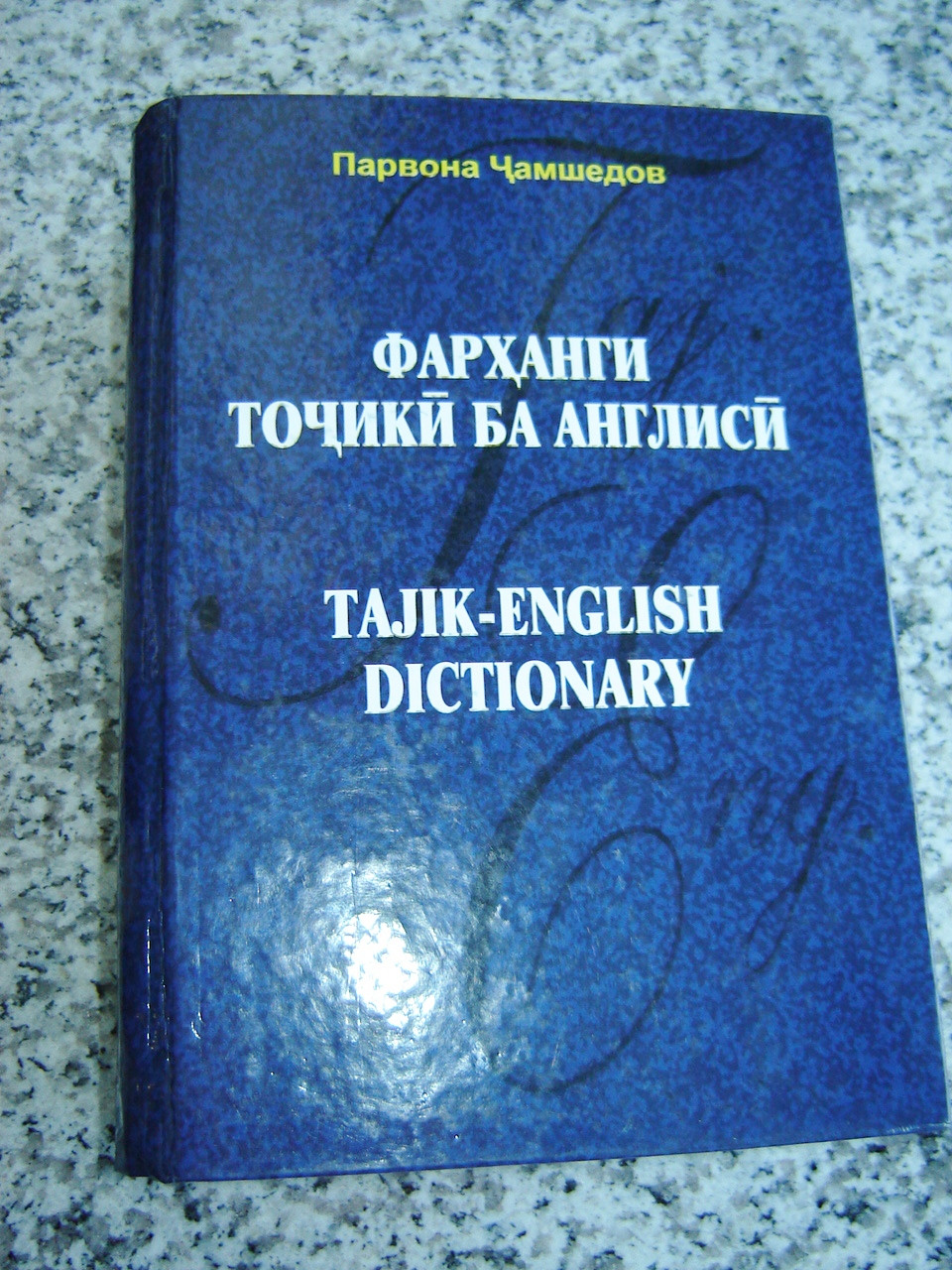

The official language spoken here is Tajik, a language that is related to Persian. Because of their historical ties to Russia, the Russian language remains to be used in business as well as in communications between different ethnic groups. There has been some debate as to whether the country should get rid of Russian or keep it, but in the end they decided to keep it around as a lingua franca.

So, if you’re a woman who hates plucking their eyebrows, then you’re in luck! Tajik women are famously known for their unibrows that would make Frida Kahlo nod with approval. And if you’re a woman who doesn’t really have one naturally, many women will take these special herbs and brush them across their brow; after it sits there for a period of time and they wipe it off, it will resemble the coveted unibrow. When asked why they like their unibrows, it’s the same reason why Western women put on make-up or paint their nails: because it’s pretty. You do you, boo.

Up next: art and literature

The name Tajikistan literally means “land of the Tajiks.” But where the term Tajik came from is up for debate. The main dispute is whether the original people were of Turkish or Iranian descent. Because of the Russian influence in its history, you may also see the name of this country written as Tadjikistan.

Tajikistan is one of the former Russian countries of Central Asia. This landlocked area is surrounded by Kyrgyzstan to the north, China to the east, Afghanistan to the south, and Uzbekistan to the west. The Tajik people are native to this area but they also lived in areas of Afghanistan and Uzbekistan as well. This country is highly mountainous: located in the Pamir Mountains, more than half the country is above 9800 ft above sea level. These mountains also give way to the Amu Darya and the Panj Rivers and over 900 lakes (Calm down, Minnesota. Your 10,000 lakes are still cool).

People have lived in these lands for a very long time. It was once part of the Archaemenid Empire and later was conquered by Alexander the Great. The Silk Road passed right through this area, and the northern parts did quite a bit of trade with China. It used to be quite religiously diverse, but once the Arabs moved into the area, it soon became an Islamic state. It changed hands so many times, from being under Persian rule to falling under Genghis Khan’s Mongol invasion to eventually, the Russians. During the late 1800s, Russia slowly moved into Central Asia with their Imperial interests at hand. The Tajiks really weren’t all that excited about the Russians being there, and there were conflicts over it. During the times following the Russian Revolution in 1917, Bolshevik forces burned down any building associated with organized religion. Much of the Tajik areas were part of Uzbekistan before breaking off to be its own republic in 1929. It was known as Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic, and their soldiers were conscripted into the Russian army during WWII. They remained under Russian control until the breakup of Russia in 1991; Tajikistan finally gained its independence. They fell into a civil war right away following their independence. A ceasefire was reached in 1997, and although they’ve held functional elections since then, it wasn’t without tension. Between tensions in their own country and the nearby war in Afghanistan, there have been troops of various nationalities stationed in the capital and other areas of the country.

Because of the civil war, Tajikistan’s economy has struggled. And struggle is probably an understatement to a degree. A little less than half of its GDP comes from remittances sent back from people who’ve moved to other countries for work (mainly to Russia). They also receive assistance from other countries, especially since droughts and other factors have led to a high number of people living with food insecurity. After the civil war ended, some industry has grown, especially in energy and utilities. Unfortunately, money from drug trafficking is a constant problem in this area.

The capital city of Dushanbe is located in the southwest corner of the country. It literally means “Monday,” named after a village that used to have a large bazaar held on Mondays. It sounds weird, but then again, we have stores named Tuesday Morning and Weekends Only. During the Communist years under Russia, it was renamed Stalinabad, after Joseph Stalin. (...See, we knew Stalin was bad. They practically spelled it out.) They generally have a Mediterranean climate since the mountains keep back a lot of the colder Siberian air. Today, it has several universities, sporting venues, shopping centers, arts centers, and museums. Dushanbe also boasts the second tallest freestanding flagpole in the world. At 541 feet, it’s only 14 feet shorter than the Washington Monument. (It’s only second to the one in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, coming in at 561 feet.)

Although technically Tajikistan is a secular country, about 96-98% of the people here are Muslim. And more specifically, they follow the Hanafi school so Sunni Islam. You’ll also find small populations of Christians (mostly Russian Orthodoxy and various Protestants), Buddhists, and Zoroastrians.

The official language spoken here is Tajik, a language that is related to Persian. Because of their historical ties to Russia, the Russian language remains to be used in business as well as in communications between different ethnic groups. There has been some debate as to whether the country should get rid of Russian or keep it, but in the end they decided to keep it around as a lingua franca.

So, if you’re a woman who hates plucking their eyebrows, then you’re in luck! Tajik women are famously known for their unibrows that would make Frida Kahlo nod with approval. And if you’re a woman who doesn’t really have one naturally, many women will take these special herbs and brush them across their brow; after it sits there for a period of time and they wipe it off, it will resemble the coveted unibrow. When asked why they like their unibrows, it’s the same reason why Western women put on make-up or paint their nails: because it’s pretty. You do you, boo.

Up next: art and literature

Saturday, January 25, 2020

SYRIA: THE FOOD

Well, I’m finally getting back to the blog. It’s taken me awhile to get back on schedule, but here I am. And with the moving and everything, I still can’t quite find everything I need, so it’s a little frustrating. That, and I’m too short to reach anything in my cabinets. But I’m determined (probably more like hardheaded) to get this thing off and running and finish up next year, even with all the difficulties of getting settled.

So, the first thing I made was Syrian Onion Bread. I started out by adding my yeast packet to 4 ½ oz of lukewarm water and let it sit for about 10 minutes to proof. Then I put my flour and salt in a bowl and mixed it altogether. After making a well in the center, I poured my yeast proof in the center and mixed to form a dough. I ended up doubling the recipe to make eight pieces instead of four. I kneaded my dough on a floured surface for about 7-8 minutes until it was really soft and stretchy, adding a bit of flour as needed to keep it from sticking. Then I put it in a lightly oiled bowl, covered it with some wax paper (since I didn’t have any cheesecloth) and let it sit in a warm place until it’s risen some. (It’s January, and my house is cold, so it was a struggle.) After about 45 minutes or so, I turned it out onto a floured surface and punched it down, kneading it a little more. Then I cut the dough into eight equal pieces, formed them into balls only to flatten them out into disks. Then I pricked the entire top of it with a fork. Using some lightly oiled wax paper, I covered them again to rest for 20 minutes. At this point, I brushed the tops of them with olive oil. In a small bowl, I mixed together finely chopped onion, cumin, coriander powder, and finely chopped mint and sprinkled it on top of the breads. I baked this at 390ºF for 18 minutes. They were a little crispier than I thought they’d be, but they were really tasty to me. The onions and cumin weren’t quite as strong as I thought they’d might be. (They were pretty good with the cucumber yogurt salad below!)

The main dish was Dawood Basha, or Syrian meatballs. You can use either beef or lamb, but I went with beef because it was cheaper. I took my ground beef and mixed it with some chopped parsley and some salt and pepper, forming them into small meatballs when it was all mixed. (Aldi only had the 96/4% super lean ground beef, which I don’t like to use for meatballs because it falls apart too easily while cooking them.) I browned my meatballs on all sides and then took them out and set them aside. Then I sauteed my onions in the drippings before adding in a can of diced tomatoes. I let it cook until it started boiling. Once that started, I added my meatballs back into it and let it simmer for another 10 minutes. Toward the end, I added in a little Bharat mix (I actually just mixed a lighter version of some cumin, cloves, black pepper, and coriander). I served this over some white rice. I think this was a hit with the whole family, even with my husband who has trouble eating tomatoes because it gives him heartburn.

To go with this, I made Mujadara, or Lentil Pilaf. I washed and covered my lentils with water, boiling them for about 15-20 minutes until they were done but still firm. I really had to make sure there was enough water in the pot for this dish. Next, I cut some onions into wedges and sauteed them in olive oil. Just when they started to turn yellowish, I took half of them out and reserved them for later. I left the others in to get brown and crispy. When that was done, I moved that off to the side. Then I washed my bulgur wheat and added it to the lentils, adding a little salt and pepper to the pot as well. I left it on medium heat until most of the water is gone. I added a little more water at that point, and then I covered this and set it on very low heat for about 10 minutes, making sure every few minutes that there’s enough water to keep it wet. When the bulgur is soft, I added my yellowed onions back into it with some olive oil and mixed it altogether and letting it cook for another 5-10 minutes, garnishing it with the crispy onions I saved. I liked this dish, oddly enough, but I think it also needed just a tad more salt to it. Or maybe some a bit of something spicy perhaps.

And to contrast these two savory dishes, I made a cool dish called Laban bikhyar, or cucumber yogurt salad. I cut up part of a cucumber into small pieces, added it in a bowl with two plain yogurt cups. Then I added in a bit of chopped mint, a little mashed minced garlic, and a little salt. To me, it tasted close to Greek tzatziki sauce. In essence, I’m sure it’s probably the same, and I’ve probably made it before. But no matter, it went well with the bread.

I thought Syria was going to be a difficult country to cover, and there were certainly stories that were difficult to read about. But I made it through. And I did come across stories of the helpers, of the regular people doing extraordinary things. Lately, I’ve become really interested in the podcast called “Today, Explained.” They did a really good job explaining the complexities of what’s going on in Syria. Somewhat dated now (it aired April 6, 2018 called “It’s never too late to understand the war in Syria”), it made me realize what an extremely sensitive situation there is over there. And it’s understandable if you’re a little fuzzy on who all the players are in this conflict. But I would definitely suggest checking it out. So, if you’re interested in learning more, please click on the link above.

Up next: Tajikistan

So, the first thing I made was Syrian Onion Bread. I started out by adding my yeast packet to 4 ½ oz of lukewarm water and let it sit for about 10 minutes to proof. Then I put my flour and salt in a bowl and mixed it altogether. After making a well in the center, I poured my yeast proof in the center and mixed to form a dough. I ended up doubling the recipe to make eight pieces instead of four. I kneaded my dough on a floured surface for about 7-8 minutes until it was really soft and stretchy, adding a bit of flour as needed to keep it from sticking. Then I put it in a lightly oiled bowl, covered it with some wax paper (since I didn’t have any cheesecloth) and let it sit in a warm place until it’s risen some. (It’s January, and my house is cold, so it was a struggle.) After about 45 minutes or so, I turned it out onto a floured surface and punched it down, kneading it a little more. Then I cut the dough into eight equal pieces, formed them into balls only to flatten them out into disks. Then I pricked the entire top of it with a fork. Using some lightly oiled wax paper, I covered them again to rest for 20 minutes. At this point, I brushed the tops of them with olive oil. In a small bowl, I mixed together finely chopped onion, cumin, coriander powder, and finely chopped mint and sprinkled it on top of the breads. I baked this at 390ºF for 18 minutes. They were a little crispier than I thought they’d be, but they were really tasty to me. The onions and cumin weren’t quite as strong as I thought they’d might be. (They were pretty good with the cucumber yogurt salad below!)

The main dish was Dawood Basha, or Syrian meatballs. You can use either beef or lamb, but I went with beef because it was cheaper. I took my ground beef and mixed it with some chopped parsley and some salt and pepper, forming them into small meatballs when it was all mixed. (Aldi only had the 96/4% super lean ground beef, which I don’t like to use for meatballs because it falls apart too easily while cooking them.) I browned my meatballs on all sides and then took them out and set them aside. Then I sauteed my onions in the drippings before adding in a can of diced tomatoes. I let it cook until it started boiling. Once that started, I added my meatballs back into it and let it simmer for another 10 minutes. Toward the end, I added in a little Bharat mix (I actually just mixed a lighter version of some cumin, cloves, black pepper, and coriander). I served this over some white rice. I think this was a hit with the whole family, even with my husband who has trouble eating tomatoes because it gives him heartburn.

To go with this, I made Mujadara, or Lentil Pilaf. I washed and covered my lentils with water, boiling them for about 15-20 minutes until they were done but still firm. I really had to make sure there was enough water in the pot for this dish. Next, I cut some onions into wedges and sauteed them in olive oil. Just when they started to turn yellowish, I took half of them out and reserved them for later. I left the others in to get brown and crispy. When that was done, I moved that off to the side. Then I washed my bulgur wheat and added it to the lentils, adding a little salt and pepper to the pot as well. I left it on medium heat until most of the water is gone. I added a little more water at that point, and then I covered this and set it on very low heat for about 10 minutes, making sure every few minutes that there’s enough water to keep it wet. When the bulgur is soft, I added my yellowed onions back into it with some olive oil and mixed it altogether and letting it cook for another 5-10 minutes, garnishing it with the crispy onions I saved. I liked this dish, oddly enough, but I think it also needed just a tad more salt to it. Or maybe some a bit of something spicy perhaps.

And to contrast these two savory dishes, I made a cool dish called Laban bikhyar, or cucumber yogurt salad. I cut up part of a cucumber into small pieces, added it in a bowl with two plain yogurt cups. Then I added in a bit of chopped mint, a little mashed minced garlic, and a little salt. To me, it tasted close to Greek tzatziki sauce. In essence, I’m sure it’s probably the same, and I’ve probably made it before. But no matter, it went well with the bread.

I thought Syria was going to be a difficult country to cover, and there were certainly stories that were difficult to read about. But I made it through. And I did come across stories of the helpers, of the regular people doing extraordinary things. Lately, I’ve become really interested in the podcast called “Today, Explained.” They did a really good job explaining the complexities of what’s going on in Syria. Somewhat dated now (it aired April 6, 2018 called “It’s never too late to understand the war in Syria”), it made me realize what an extremely sensitive situation there is over there. And it’s understandable if you’re a little fuzzy on who all the players are in this conflict. But I would definitely suggest checking it out. So, if you’re interested in learning more, please click on the link above.

Up next: Tajikistan

Sunday, January 19, 2020

SYRIA: MUSIC AND DANCE

At one time, Syria was the cultural center for Arab classical music, a center for musical innovation. Cities like Damascus, and especially, Aleppo, cultivated musicians and perpetuated traditional folk styles.

Syria is known for its muwashshah music. This genre originated during the Medieval times and was created as an accompaniment to the Andalusian muwashshah poetry. This poetry typically consisted of five stanzas that alternated between the refrain. If you were a muwashshah musician, the northern Syrian city of Aleppo was the place to be. Sadly, Aleppo has been hit hard in the Syrian Civil War.

In most folk music traditions, you’ll often hear the oud performed. This long-necked stringed instrument is related to the lute. Flutes are also fairly popular. Syrian music uses several types of handheld drums and percussion instruments like the darbouka (type of goblet drum), riq (type of tambourine), and daf (type of frame drum). Other instruments you may hear either solo or in an ensemble include the qanun (type of zither), zurna (type of wind instrument related to an oboe), rebab (type of bowed stringed instrument), and the kamanjah (stringed instrument related to a rebab).

Since Syria is one of the places where Christianity originated, Syrian Christians developed their own style of chanting and other liturgical music. There was also a sizable following of Syrian Jews who also developed their own unique style of music.

Dancing has been enjoyed at weddings and other joyous ceremonies since antiquity. The Dabke, a combination of a circle dance and a line dance, is a popular dance in Syria as well as some other nearby countries. There are quite a few variations depending on what region you live in and whether you’re a man or a woman. They’re also known for the Arada, a type of sword dance, and an oriental dance for women.

| Farid al-Atrash |

I listened to a few Syrian musicians on Spotify, some older musicians and a few modern ones. The first one I sampled was Farid al-Atrash. He was an accomplished oud player and actor. He moved to Egypt in his youth, he recorded nearly 500 songs and acted in 31 films.

Fahd Ballan was another singer and actor, working during the same times as Farid al-Atrash. In fact, they worked together at times. Even though he also moved to Egypt to work, the majority of his songs were sung in his native Hourani dialect of southern Syria.

|

| Sabah Fakhri |

|

| George Wassouf |

|

| Mayada El Hennawy |

Mayada El Hennawy comes from a musical family, so it was no wonder she was invited to perform in Egypt as a young adult. She comes from Aleppo, where so many other musicians also share their musical roots. And she’s also been performing for decades.

|

| Assala Nasri |

|

| Bu Kolthoum |

One rapper I found was Bu Kolthoum. I really liked what I heard from him. The background was sort of chill, with a slight jazz feel in certain songs. Making use of some sampling and conversations, it made each song seem unique. I have no idea what he’s rapping about, but it had a nice flow and beat. I read an article that he moved to Jordan and now uses his music as a response to the crisis in his home country. It's well done. I’m gonna play it in the car since I found a lot of his stuff on Soundcloud.

Up next: the food

Friday, January 17, 2020

SYRIA: ART AND LITERATURE

Arts have been a part of this region for several millennium. Handicrafts and tools have been built and created since antiquity. Once Islam became the dominant religion of Syria, that impact on art had changed. One of the aspects of Islam is that it forbids any kind of depiction or drawing of people or animals. So, essentially, prior to the early 20th century, much of their visual arts were geometric shapes, tessellations, and calligraphy. Sculptures out of marble and other materials are often seen outside of public buildings and palaces.

Metalwork, used in jewelry, cookware, and other tools, was really important. Jewelry mainly utilized gold and silver, but metals like copper and brass were used for plates, bowls, and other objects. Much of the metalwork art had originally been done by Syrian Jews.

Mosaic woodworking is another art that was highly popular. Using woods of different colors and textures created beautiful works of art, mainly as tables, chairs, desks, trays, game boards, boxes, etc.

Other arts include glassblowing (which I’d love to learn to do) and fabric making. A type of silk with floral patterns that show on both sides called damask is actually named for the city of Damascus where it was first produced. The Bedouins are also known for their weaving abilities, especially when it comes to prayer rugs and carpets.

The ancient city of Ugarit, near present-day Latakia, held long-forgotten ruins that were found by accident. What these accidental discoverers found were ancient texts, leading them to realize later they created their own cuneiform alphabet dating back to around the 14th century BC. Although written in a different script, the order of the alphabet is fairly similar to the order of the English alphabet as we know it today.

Today, and for a very long time, the vast majority of Syrian literature is written in Arabic. Much of the early examples of literature were in poetry, a genre that is very much a deep part of the broader Arab culture. However, most examples of literature stemmed after the nahda, a literary revival that took place during the late 19th century and early 20th centuries. It’s tied to a change toward more modernism, enlightenment, and cultural reform.

|

| Adonis |

Syria literature enveloped many of the same writing genres that were popular in Europe, the Americas, and the Middle East. If the 19th century focused on romantic literature, then the 20th century changed that. Social realism became an important genre for Syrian writers, addressing issues like recent wars and their place in the Arab community. Other genres that emerged during the 20th century include historical novels, magical realism, and science fiction.

Some authors of note to look for include Adonis (poet, translator), Muhammad al-Maghout (writer, poet), Haidar Haidar (novelist), Ghadah al-Samman (journalist, novelist), Nizar Qabbani (poet, diplomat -- read his poem "Balqis" about his wife who was killed in the 1981 bombing of the Iraqi embassy in Beirut. Very powerful, emotional), Zakaria Tamer (short story writer), Fawwaz Haddad (novelist), and Salim Barakat (novelist, poet). |

| Nizar Qabbani |

Up next: music and dance

Saturday, January 11, 2020

SYRIA: THE LAND AND THE PEOPLE

You don’t have to be a news junkie to know that Syria has been in the news quite a bit over the past ten years, and especially in recent months. This area has long stood center stage in conflict, an unfortunate position for its people and rich cultural heritage. In an effort to understand this country and the situation a bit more, I thought I’d take the Howard Zinn approach and dig in a bit on the silent victims: their cultural and culinary arts.

The origin of the name Syria is thought to have been stemmed from several sources, but generally seems to lead back to Greek, derived from variations of Assyria. The borders have changed over time, but the land known as Syria was designated to being along the eastern part of the Mediterranean.

Today, Syria is located in The Levant, the area between the eastern side of the Mediterranean and north of the Arabian Peninsula. It’s surrounded by Turkey to the north; Iraq to the east; Jordan to the south; and Israel [near the Golan Heights] and Lebanon to the west. It also shares part of its western coastline with the Mediterranean Sea. The Euphrates is a major river that winds its way through Syria and is one of the most important rivers in the region. Its climate ranges from arid desert to a semiarid steppe climate, although the areas along the coast and along the rivers are fairly fertile.

Syria lies in the region where many facets of civilization were born. Agriculture and cattle breeding were a couple of the things that were developed in this area since 10,000 BC. There is also evidence of tools and trading from this time. Several kingdoms were all vying for dominance for many centuries, but they were also subject to foreign invasions as well. Eventually most of this area fell under the Neo Assyrian Empire, which brought in Aramaic as their lingua franca until the Arab Islamic movement took over in the 7-8th centuries AD. The Greeks, under Alexander the Great, took over in 330 BC and gave it its name of Syria. It later became part of the Roman Empire, and then the Byzantine when the Roman Empire split up. Christianity became the main religion and many areas in Syria are significant in Christian history (Paul’s conversion took place along the Road to Damascus). Muhammad traveled through this area, and not long after was incorporated under the Umayyad Dynasty and later Abassid Dynasty. During this time, Arabic became the official language. The Middle Ages were marked by the Crusades and other periods of attacks and fighting for the land, some (much?) of it linked to the trade routes along the Silk Road (when they discovered a sea route, they didn’t worry about that so much). During the early 1500s, the Ottomans ventured into this area, and it was actually pretty peaceful among all the different ethnic groups here. As they entered WWI, the Ottomans were tied to the Armenian and Assyrian Genocides, and at the end of the war, it was placed under a French mandate. After a series of revolts, Syria finally was granted its independence in 1946. Not long into their independence, they launched an attack on Palestine to destroy Jewish towns. After a series of coups and in the aftermath of the Suez conflict, Syria welcomed Russia’s help, but that made some other countries nervous. The Ba’athist Party took over in the early 1960s, followed by several wars involving Egypt, Israel, Syria, and Lebanon from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. There’s been a civil war in Syria since the early 2000s, and millions have fled the conflict as refugees.

The capital city of Damascus is located in the southwest corner of the country. It’s also one of the oldest, continuously lived in cities in the world, with references to it dating back to the 15th century BC. The old city, including what’s left of its ancient walls and gates, is listed as part of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites. It used to be the second-largest city in Syria behind Aleppo, but the war may have changed that now. Damascus is listed as being in a cold desert climate, which means if you like frequent sunshine and low humidity for much of the year, this is it. The vast majority of the people living here are Syrian Arabs, with Kurds as the largest minority. Damascus is a cultural capital, boasting many colleges and universities, museums, sports arenas, resorts, restaurants, and shopping areas.

Although largely dependent on oil and agriculture, the Syrian Civil War has had a devastating effect on its economy. One major source of revenue was from phosphate mining, but Syria lost that to ISIS several years ago. They mainly rely on credit from their main trade partners: Russia, Iran, and China. The once thriving tourism industry has fallen drastically while unemployment and poverty rates soar. Struggling against global sanctions from the US and Europe, the oil industry has also taken a hit.

Nearly three-quarters of Syrians are Sunni Muslims, mostly from the Sunni Arabs, although there are also Kurds and Turkoman populations in there. There are smaller numbers of Shia Muslims, Christians, and other religions.

The official language is Arabic, and several dialects are used in Syria. Mainly the Levantine dialect is heard in the western portions of the country while the Mediterranean dialect is used on the northeastern side. There are quite a few minor languages spoken here, but none carry any kind of official status. English and French are widely studied as foreign languages, with English being the dominant one.

The conflict in Syria and its history are complicated, much too complicated to give it any justice in this blog post. The problem with countries that have been inhabited for thousands and thousands of years is that there is a ton of history that goes with it. I read an article once about the threat of looting antiquities from the bombed out libraries and museums. The somewhat good news is that due to the bravery of a few, much of it has been saved, but I imagine some collections may never be whole again. In October 2018, the National Museum of Damascus reopened after being closed for nearly seven years. We know who the true heroes are.

Up next: art and literature

The origin of the name Syria is thought to have been stemmed from several sources, but generally seems to lead back to Greek, derived from variations of Assyria. The borders have changed over time, but the land known as Syria was designated to being along the eastern part of the Mediterranean.

Today, Syria is located in The Levant, the area between the eastern side of the Mediterranean and north of the Arabian Peninsula. It’s surrounded by Turkey to the north; Iraq to the east; Jordan to the south; and Israel [near the Golan Heights] and Lebanon to the west. It also shares part of its western coastline with the Mediterranean Sea. The Euphrates is a major river that winds its way through Syria and is one of the most important rivers in the region. Its climate ranges from arid desert to a semiarid steppe climate, although the areas along the coast and along the rivers are fairly fertile.

Syria lies in the region where many facets of civilization were born. Agriculture and cattle breeding were a couple of the things that were developed in this area since 10,000 BC. There is also evidence of tools and trading from this time. Several kingdoms were all vying for dominance for many centuries, but they were also subject to foreign invasions as well. Eventually most of this area fell under the Neo Assyrian Empire, which brought in Aramaic as their lingua franca until the Arab Islamic movement took over in the 7-8th centuries AD. The Greeks, under Alexander the Great, took over in 330 BC and gave it its name of Syria. It later became part of the Roman Empire, and then the Byzantine when the Roman Empire split up. Christianity became the main religion and many areas in Syria are significant in Christian history (Paul’s conversion took place along the Road to Damascus). Muhammad traveled through this area, and not long after was incorporated under the Umayyad Dynasty and later Abassid Dynasty. During this time, Arabic became the official language. The Middle Ages were marked by the Crusades and other periods of attacks and fighting for the land, some (much?) of it linked to the trade routes along the Silk Road (when they discovered a sea route, they didn’t worry about that so much). During the early 1500s, the Ottomans ventured into this area, and it was actually pretty peaceful among all the different ethnic groups here. As they entered WWI, the Ottomans were tied to the Armenian and Assyrian Genocides, and at the end of the war, it was placed under a French mandate. After a series of revolts, Syria finally was granted its independence in 1946. Not long into their independence, they launched an attack on Palestine to destroy Jewish towns. After a series of coups and in the aftermath of the Suez conflict, Syria welcomed Russia’s help, but that made some other countries nervous. The Ba’athist Party took over in the early 1960s, followed by several wars involving Egypt, Israel, Syria, and Lebanon from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. There’s been a civil war in Syria since the early 2000s, and millions have fled the conflict as refugees.

The capital city of Damascus is located in the southwest corner of the country. It’s also one of the oldest, continuously lived in cities in the world, with references to it dating back to the 15th century BC. The old city, including what’s left of its ancient walls and gates, is listed as part of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites. It used to be the second-largest city in Syria behind Aleppo, but the war may have changed that now. Damascus is listed as being in a cold desert climate, which means if you like frequent sunshine and low humidity for much of the year, this is it. The vast majority of the people living here are Syrian Arabs, with Kurds as the largest minority. Damascus is a cultural capital, boasting many colleges and universities, museums, sports arenas, resorts, restaurants, and shopping areas.

Although largely dependent on oil and agriculture, the Syrian Civil War has had a devastating effect on its economy. One major source of revenue was from phosphate mining, but Syria lost that to ISIS several years ago. They mainly rely on credit from their main trade partners: Russia, Iran, and China. The once thriving tourism industry has fallen drastically while unemployment and poverty rates soar. Struggling against global sanctions from the US and Europe, the oil industry has also taken a hit.

Nearly three-quarters of Syrians are Sunni Muslims, mostly from the Sunni Arabs, although there are also Kurds and Turkoman populations in there. There are smaller numbers of Shia Muslims, Christians, and other religions.

The official language is Arabic, and several dialects are used in Syria. Mainly the Levantine dialect is heard in the western portions of the country while the Mediterranean dialect is used on the northeastern side. There are quite a few minor languages spoken here, but none carry any kind of official status. English and French are widely studied as foreign languages, with English being the dominant one.

The conflict in Syria and its history are complicated, much too complicated to give it any justice in this blog post. The problem with countries that have been inhabited for thousands and thousands of years is that there is a ton of history that goes with it. I read an article once about the threat of looting antiquities from the bombed out libraries and museums. The somewhat good news is that due to the bravery of a few, much of it has been saved, but I imagine some collections may never be whole again. In October 2018, the National Museum of Damascus reopened after being closed for nearly seven years. We know who the true heroes are.

Up next: art and literature

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-8113478-1507627463-4101.jpeg.jpg)