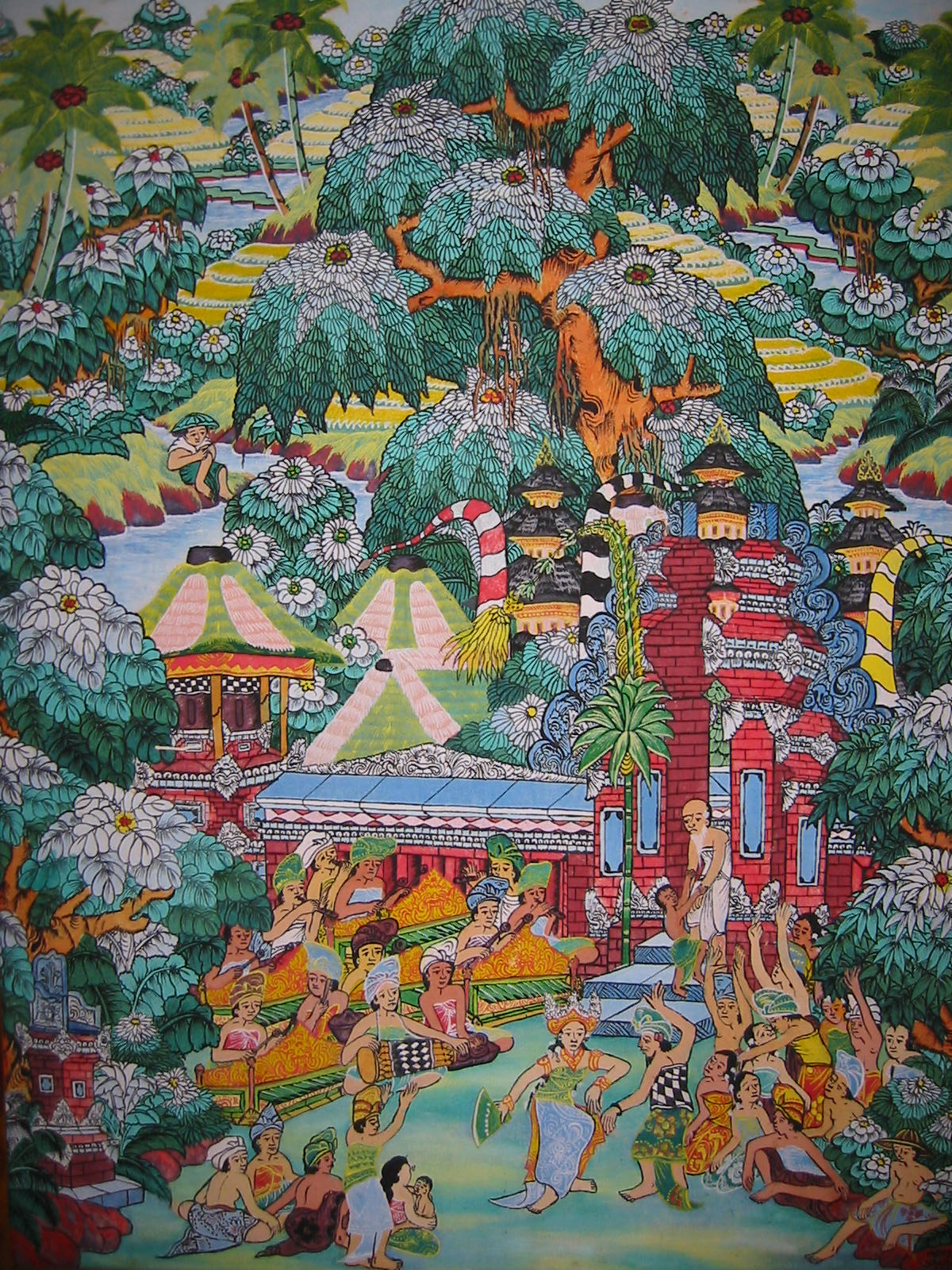

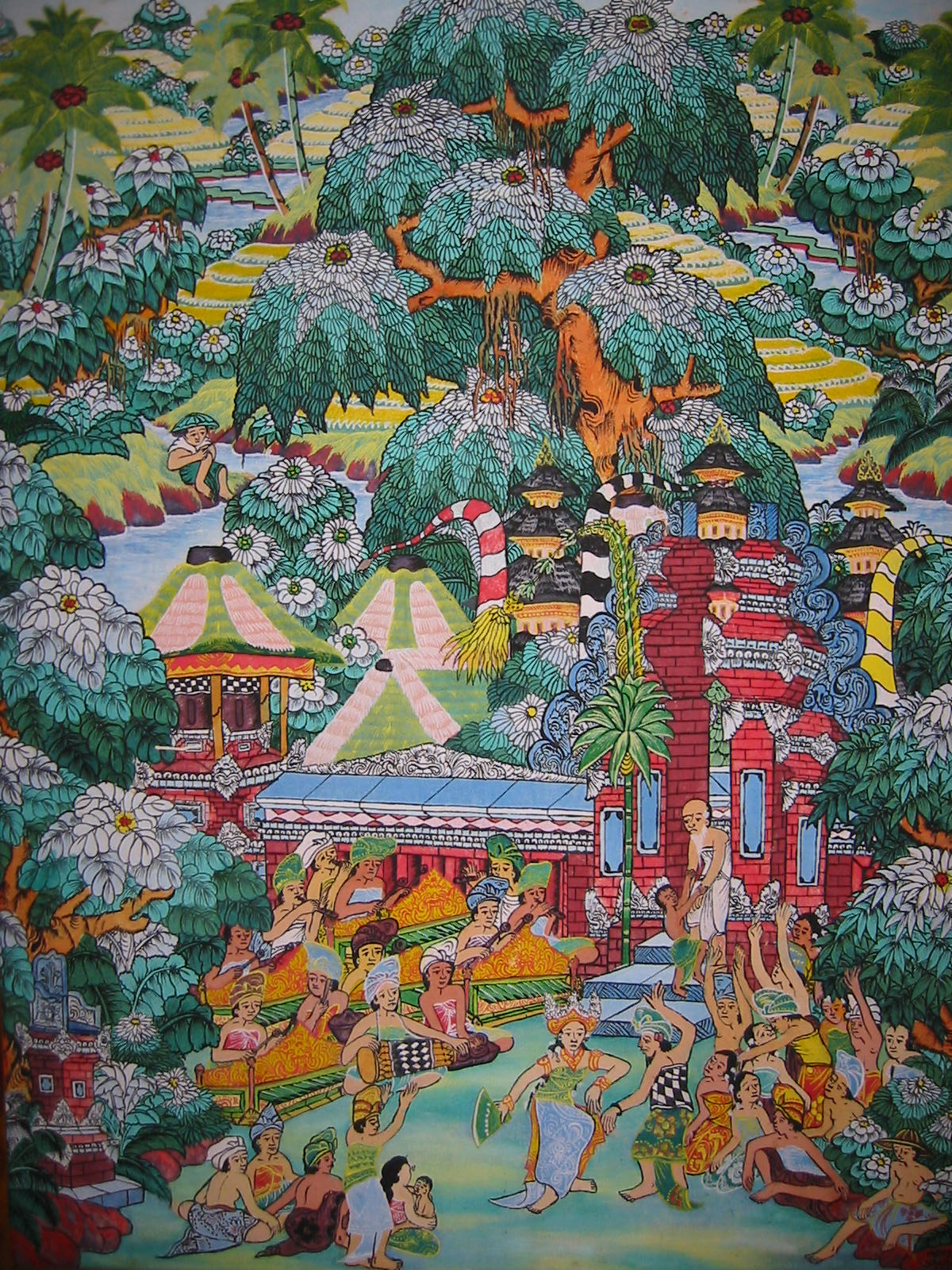

Early art in

Indonesia was pretty much relegated to being religious in nature. Generally

speaking, it was more or less centered around Hindu deities and important

stories; however, there are also plenty of Buddhist-centered art as well. There were also decorative motifs as

well, mostly with natural themes that include leaves, flowers, and local

animals.

When the Dutch

arrived, they introduced European art techniques to the native Indonesians.

However, when the Dutch used the term “Indonesian painting,” it didn’t solely

refer to paintings by Indonesians, but also for Dutch and other foreign artists

who were living in Indonesia (called Dutch East Indies at that time) as

well. The late 1800s into the

early 1900s saw a period of popularity in Balinese art. It was often considered

one of the most vibrant styles of art in this area.

|

| by Inombong Sayad Ubud |

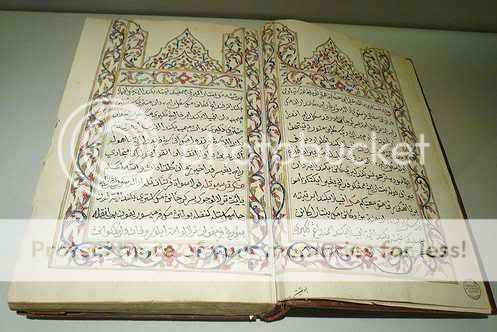

During the latter

part of the 20th century, Indonesian art began to become influenced

by several styles of art, namely European-inspired abstract expressionism and

Islamic-based art. As Indonesia began the search for a national identity among

its multi-ethnic cultures, much of the frustration and self-finding sentiments

were reflected through the artist’s paintbrush.

Sculpture was also

an important medium of art in Indonesia. There are many examples of sculptures

dating back to the earliest of days. Each island essentially has its own

culture and language and indigenous belief systems, so the styles can vary

greatly from island to island, ranging from wooden sculptures to masks to

sculptures similar to totem poles. With the introduction of Hinduism and

Buddhism, artistic sculptures began to reflect this new reign of thought.

Temples and shrines were the main sites for these religious-based sculptures of

deities and other religious objects and symbols. The Temple of Borobudur in

central Java is famous for its frescos of hundreds of stone buddhas. Other

sites show a strong Hindu influence. Today, the majority of carvings and

sculptures are in the form of souvenirs for tourists as well as elaborate

folding screens.

Indonesia has some

very unique architecture as well. Although much of it was influenced from

India, there were also other notable influences as well. Probably the most well

known style can be seen in the stilt houses. Used in areas of Sumatra, Borneo, Minangkabau, Sulawesi,

these stilt houses were elevated on poles for a number of reasons: to guard

against flooding, to keep certain rodents out, and to give a cool place to work

or store items. Many of these houses had highly peaked roofs called saddle

roofs; it has points protruding upwards that looked as if someone pulled the

roof toward the sky like taffy. Some of these houses (usually those belonging

to a higher social status) are surrounded by highly decorated walls.

|

| Example of songket |

And of course,

there were a number of handicraft-like items. Indonesia is famous for its

cloth, and there are a few different types of traditional cloth that are

produced here. The first one is batik, which utilizes a technique of using wax

to create patterns on the cloth before adding the dye. Ikat is another type of dying

process where either the warp fibers (lengthwise fibers) or the weft fibers

(the ones that are being wove into the warp fibers) are dyed prior to weaving.

Songket is a type of weaving that is commonly found in Indonesia but also in

Malaysia and Brunei. This beautiful cloth is usually silver or gold threads

wove into silk or cotton. The islands of Java and Bali are also well known for

their making of the kris, a curvy-bladed dagger. Some people have a religious

ritual that accompanies the making and use of this weapon, and the hilt (the

handle) and sheath are often highly decorated. It’s also surrounded by special

superstitions that it holds magical powers or that some kris are have good

auras while others have bad ones.

_3.jpg)

The literature of

Indonesia is somewhat of a confusing term. In general, it refers to literature not only in Indonesia

but also includes Malaysia and Brunei.

And Indonesian literature is written in a multitude of languages: early

literature was almost entirely written in Malay, but it also includes works

written in Indonesian, Javanese, Sundanese, Batak, Balinese, Madurese, or even

Dutch or English. Malay and Indonesian are very similar languages and different

dialects of both languages are fairly intelligible to many speakers.

There were a lot of

different periods of Indonesian literature. Traditional literature was normally marked as being after

the introduction of Islam, but before the modern period of the 20th

century. Prior to this period, stories and histories were pretty much oral at

that point. Then you also have older Malay literature, which was generally from

around 1870 to 1942. During this time, many popular American and European

novels were being translated as well as syair poetry and highly romanticized

stories called hikayat.

The early 20th

century brought about a lot of changes. First, the Indonesian language was

introduced as a lingua franca, unifying all of the islands. Although Malay had

commonly been used as a lingua franca, it was by no means a national language.

The Balai Pustaka was formed; it was this government-sponsored agency that was

responsible for promoting and publishing literature. It was in response against

the Dutch; however, it came at the cost of much censorship. The first

Indonesian novels were published during this time with the help of the Balai

Pustaka.

From about 1933, an

era called the New Literates emerged. Many of the young intellectuals began to

sense a change in what was acceptable as literature. They knew a change needed

to happen but distrusted the Balai Pustaka because it was run by the government.

The answer came in the form of Indonesia’s first literary magazine, lasting

into the early 1950s. By the end of WWII, Indonesian writers were focused more

on their own independence and writing about the pressing political matters of

the day; literature was far more realistic in style.

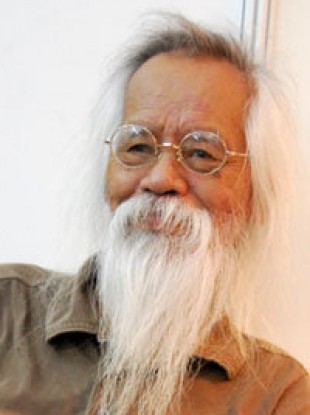

|

| author Remy Sylado |

Short stories and

poetry dominated through the 1950s, and by the mid-1960s, writers who were

associated with leftist groups left Indonesia and began to write from abroad.

The romance novel was the hot genre during the 1980s and 1990s, and previously

quasi-taboo subjects such as femininity and gender identity became common

themes in short stories and novels.

Although there have

been many foreign authors using Indonesia as the setting for their novels (such

as The Twenty-One Balloons by William

du Bois), there have been a plethora of authors that people on the Internets

seem to mention. I did find a nice

list with comments from The Guardian

dated in 2011, and it’s worth taking a look at here. It’ll at least point you in the right

direction for finding something to read.

As if you have that problem.

Up next: music and

dance

_3.jpg)