For many Burkinabé, living off the land by farming or

raising cattle is a way of life that goes back centuries. And during the dry

season (from about November to April), the ground is so dry, many people either

leave the country to look for other work, or stay and make the most of it doing

other things. During this “down time” when the daytime temperatures can reach

over 100F (37.8C), many people stay in the shade and engage in the local arts,

one of them being mask making. Most of the masks are made from the wood of the

cotton tree, or ceiba. It’s a soft wood, making it light and easy to carve,

which is good considering some of the masks can be quite large and quite

elaborate. Unfortunately, insects also like these soft woods for many of the

same reasons, so each year these masks have to be carefully soaked to prevent

damage and kill any insects that may have started. Fibers from different kinds of hemp plants

are soaked and plaited together to make the “fur of the mask” and other parts

of the costume that goes with it. These fibers may also be dyed with other

natural pigments prior to affixing it to the mask and costume. Each mask is

then decorated with a myriad of geometrical shapes and colored mostly with red,

black, and white pigments (from natural mineral and vegetable matter). These

masks generally stay in the family and are passed from father to son. Most of

the time, these masks make their appearance at burials/funerals and other life

events, but sometimes it’s simply just to entertain. Different groups of people have slightly

different techniques and designs and even colors (and some groups never really

participated in the mask making), but all in all the fabrication of it is

generally the same.

Another interesting art is that of making brass portraits of

deceased Mossi emperors. These traditions are centered near the town of

Lumbila. Tradition holds that the living emperor should never see the cast of

the previous emperor nor know the identity of the artist who created it, lest

he should die also. (Apparently, they consider these artists like demigods.)

They have a special place to work and not even the village chief is allowed to

disturb them. (I wish I had a work environment like that.)

Since about three-quarters of the population are considered

illiterate, the oral tradition of storytelling is quite a long-standing art

form in Burkina Faso. The first written

work was published in 1934 by Dim-Dolobsom Ouedraogo, entitled “Maximes,

Thoughts and Riddles of the Mossi,” a first account of recording their

traditional stories. After the country

gained its independence, writers such as Nazi Boni and Roger Nikiema came onto

the scene. During the 1970s, many

Burkinabé writers emerged as playwrights, and theatre and film became very

popular.

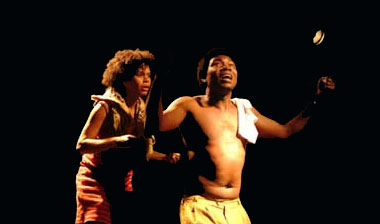

Early traditional theatre consisted of wearing masks and

also incorporates dancing, and for the most part the actors are representing

various spirits in the spirit world. Because the French took control of this

area, a lot of their cultural arts mixed with the local culture. During the

1950s, large competitive drama festivals starting taking place, and even the

church started using theatre as a means of spreading its word. There are several

theatrical and drama schools in Ouagadougou that have been open since the 1990s.

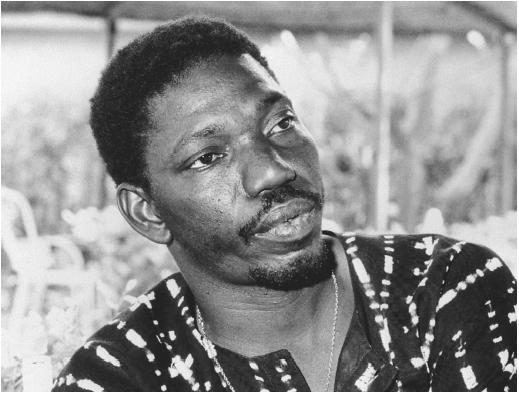

Every year, a Pan-African film fest called FESPACO held in

the cultural center of Ouagadougou – the largest film fest in Africa. Two of

the most prolific filmmakers that came out of Burkina Faso are Idrissa

Ouedraogo and Gaston Kaboré (seriously, this is the best name ever). I tried to

look up some films on Netflix, but there weren’t that many available. I mean,

there were some listed, but Netflix didn’t list an availability date and gave

me the option to save it. Wonder when that’ll be. When I retire? Bleh. Until

then, I must wait…

Up next: Music and Dance

No comments:

Post a Comment