The earliest art

found in Mongolia was cave and rock drawings. It mainly depicted their nomadic lives of

the time. Once Buddhism was introduced to the people here, most of the art from

that point forward was tied to their religious stories and characters. This

pretty much lasted up until the 20th century.

Buddhist art

generally fell into a number of mediums. One common art form was the thangka

(sometimes spelled a number of other ways). It’s essentially a painting on a

piece of cloth, typically of either a deity or some other religious symbol or

scene. It wasn’t framed, but rather rolled up like a scroll. Sometimes it’s

imprinted like an appliqué. Sculptures were also created in a variety of

different sizes and materials. Bronze was typically the most common material

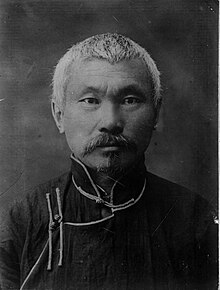

used for sculpting Buddhist deities. A spiritual leader by the name of

Zanabazar (which I keep reading as Zanzibar) was quite influential in the art

of the 17th century.

During the 19th

century, art started to change. An artist by the name of Marzan Sharav began to

implement more realistic styles of painting. As the country changed its

socio-political views and their government adopted communism, socialist realism

became the thing. However, many of the thangka-like religious paintings

suddenly began being produced as secular paintings. Artists who tried to push

modernism were subject to harsh censorship and criticism and were dealt with

accordingly. Today, artists enjoy more artistic freedom and delve into a

variety of different styles.

The vast majority

of literature in Mongolia is written in the Mongolian language. There really

isn’t that much literature preserved from the times when the Mongol Empire

reigned. However, one notable exception is that of The Secret History of the Mongols. (I suppose it’s not so secret

now, is it?) It’s the oldest piece of Mongolian literature there is, that we

know of. Even though there are portions of this that contain much older poetry.

This work is so significant that it’s not only considered a classic in

Mongolian literature but in world literature as well.

A few other

portions of poems and literary works have been found from these early

centuries, but not very many. Most of it fell into the category of epic poetry,

genealogy, and stories of epic heroes. As Buddhism began to spread its way

across Mongolia, religious texts also appeared in Mongolian as well. Many of

these were also translations of texts from India, China, and Tibet.

As Mongolia aligned

with Russia and became a communist nation, important Russian works were

translated into Mongolian. Tseveen Jamsrano was a leading Buryat (an ethnic

group living in the northern part of Mongolia and Siberia) scholar and

politician who was also a writer, journalist, editor, and translator.

Religious theatre

has had a presence for several centuries. One popular story line is the

character Milarepa, a Tibetan hermit. These plays were especially popular

during the 18th and 19th centuries. The oldest one, “Moon

Cuckoo” by Danzanravjaa, was written in 1831 (even though it got lost during

the early part of the 20th century). Theatre companies started

popping up during the 20th century and lasted even during the

communist years to today.

Some authors of

note to look for include Begziin Yavuukhulan (famous poet), Dashdorjiin

Natsagdorj (often considered founder of modern Mongolian literature), Vanchinbalyn

Injinash, Byambyn Rinchen, Ayurzana Gun-Aajav, Lodongiin Tudev, Chadraabalyn Lodoidamba,

Galsan Tschinag, and Mend-Ooyo Gombojav.

Up next: music and

dance

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment