Because of its religious diversity, you'll find both Muslim and Christian holidays celebrated in Burkina Faso.

New Year’s Day. January 1. New Years in Burkina Faso is

celebrated with big parties spent with friends and family. Despite creed,

tribe, or background, everyone comes together to bring in the New Years. It’s

the biggest celebration of the year in many places.

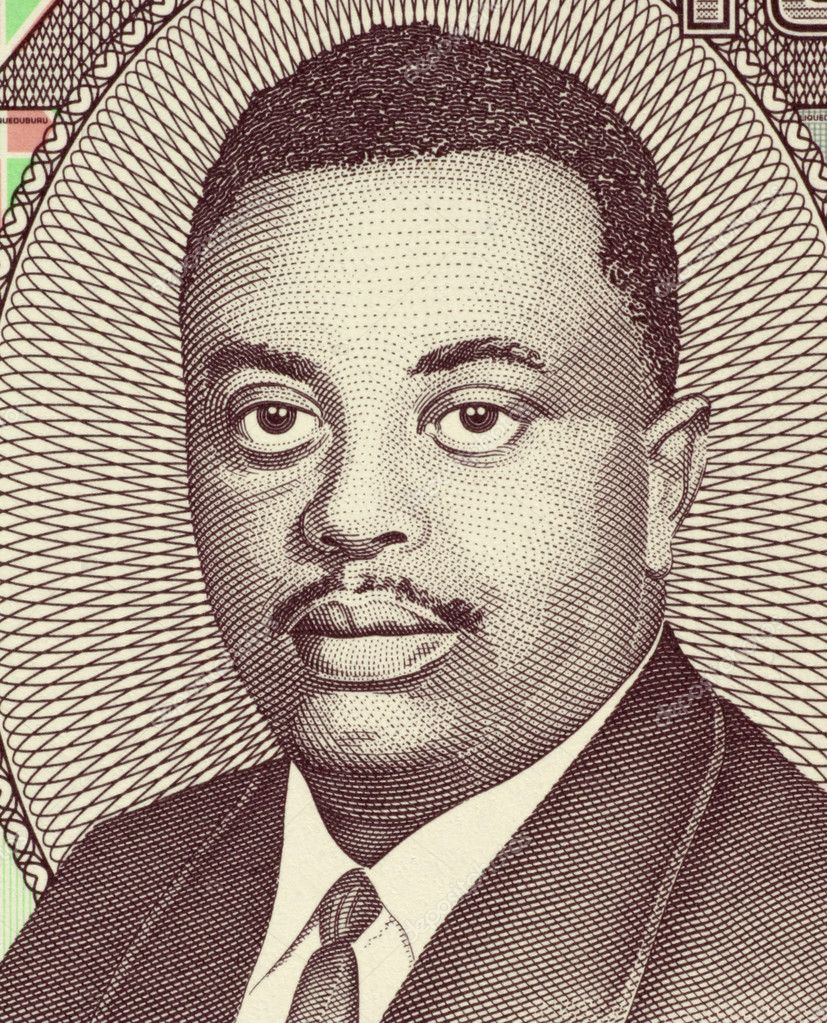

Anniversary of the 1966 coup d’etát. January 3. Only six

years after Burkina Faso declared its independence from France, a military coup

took place. The coup got rid of the

first president Maurice Yaméogo and all of the members of the National

Assembly, as well as suspended the constitution. In his place, they put Lt.

Col. Sangoulé Lamizana as the head of the government. The Army remained in

control for four years before they decided to go to a more civilian-based

government. Lamizana remained in power throughout the 1970s and won re-election

in 1978.

Women’s Day. March 8.

In Burkina Faso, people get the day off of work to celebrate. This is an

international holiday, so celebrations vary across the world. In many

countries, giving flowers is customary, but as to what flowers are given

generally depend on the country and what’s in season. But it’s also a day to

address women’s issues, such as equal pay for equal work, gender

discrimination, and women’s health issues. Many cities will have community events such as

blood drives, health screenings, and educational forums.

Easter. Varies. For the Christians, people will often start

the day off with a service at their church. Many people will also celebrate

with a large meal afterwards with friends and family.

Easter Monday. Varies. For most people, Easter Monday is a

day of rest. In Burkina Faso, people have the day off of work and school to do

so. They may also make use of this day to spend doing recreational activities

with friends and family.

Labor Day. May 1.

This is a holiday in honor of the worker. It’s often a time to discuss labor

issues, but most people use this as a day to spend relaxing with their families

and friends.

Revolution Day. August 4. It’s a holiday that is celebrated in

conjunction with Independence Day, which is celebrated the next day. It was

originally in regards to the original revolution that took place in 1960 which

led to Burkina Faso’s independence. Of course, there have been several other

revolutions since then.

Independence Day. August

5. This day marks the day that Burkina Faso gained its independence from

France. It still is a poor country, but economically speaking, it is making

small, yet consistent gains each year. Each year, everyone makes an oath to keep

peace in their country: it seems like it’s working to some degree, given that

there are about 60 different ethnic groups and a myriad of different religions.

Eid ul-Fitr. Varies. This is a Muslim holiday that

celebrates the end of Ramadan, the month of fasting. People will often go to

the mosque for special prayers. On this day people make a huge feast of a meal

and celebrate it with friends and family.

Assumption. August

15. This is a Christian holiday that is centered around the assumption that

this is the day the Virgin Mary had ascended into Heaven. Many people will

attend a special service at the church, and may participate in a variety of

Christian traditions surrounding the holiday.

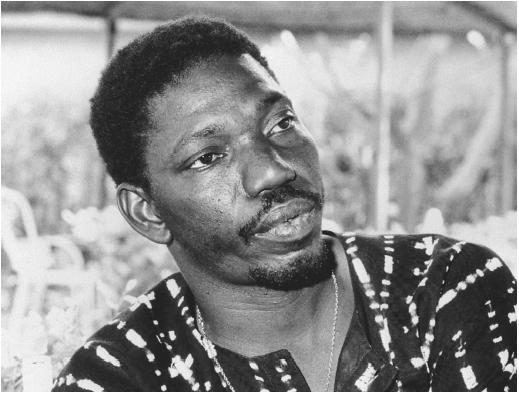

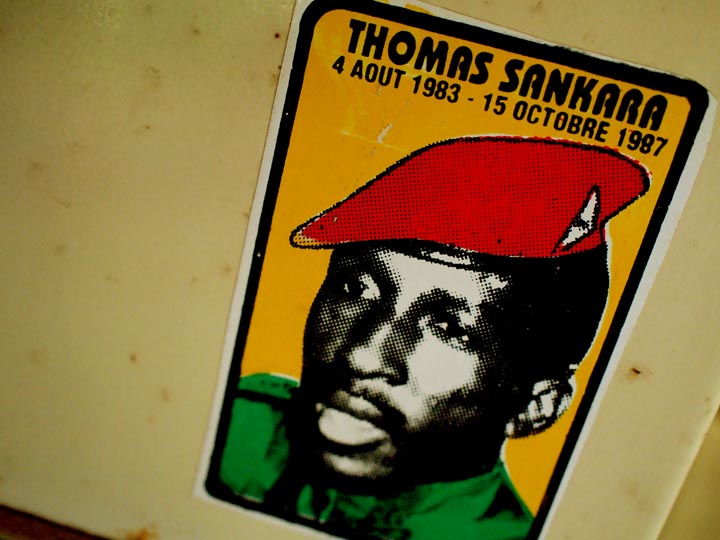

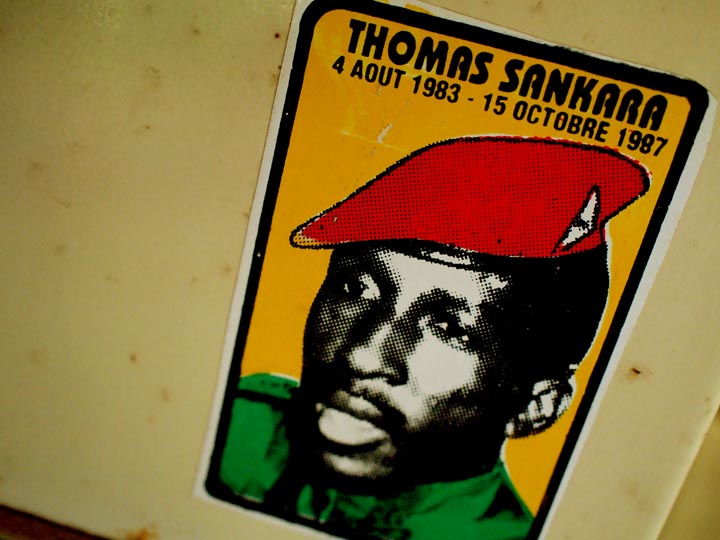

Anniversary of the 1987 coup d’etát. October 15.

In 1983, Thomas Sankara, along with Blaise Compaoré (the current

president), staged a coup to take over the short-lived Ouédraogo

administration. Sankara was the one who changed the country’s name to Burkina

Faso. Three years later, another coup was staged and Sankara was killed as a

result. Compaoré moved up and gained control, and a lot of people reported he

had something to do with Sankara’s death and with the staging of the coup. He’s

been in power since the 1987 coup, and it’s reported that he’s a very wealthy

man, despite the fact that the country he governs is the third least-developed

country in the world.

Eid ul-Adha. Varies. Also known as Tabaski in Burkina Faso (not

to be confused with Tabasco, one of my favorite condiments). It’s also known as

the Great Feast and can last up to three days for those who do not go on a

pilgrimage during this time. It’s a

celebration in honor of Abraham’s almost-sacrifice of his only son. For many Muslims around the world, an animal

is sacrificed, and a third is given to family, a third is kept, and a third is

given to charity. Nowadays, it may also

be customary to give to local community food banks or other charitable

organizations.

All Saints Day. November 1. One of the Christian holidays

(especially for Catholics); it’s a holiday designated towards homage to all the

saints, and especially to the saints who do not have their own designated days

throughout the rest of the year.

Proclamation of the Republic. December 11. This is a national day in Burkina

Faso. Although the country actually

declared its independence on August 5, 1960, December 11 was the day which

Upper Volta became an autonomous region within the French Community two years

prior to its independence. Parades march

through the streets and the flag is proudly displayed throughout the land. The

government foots an expensive bill for elaborate celebrations, despite the fact

that it continually ranks low on human development.

|

| I had to laugh at the snowman, because when was the last time Burkina Faso saw snow? |

Christmas. December

25. Christmas tends to be celebrated more in the cities rather than out in the

rural areas. The Virgin Mary plays a key

role in Christmas celebrations, and can even be seen parading through the

streets to church in the back of a truck. Christmas songs fill the air. They believe that Pere Noel (Father

Christmas) brings gifts to children and families on December 23. Special meals

with chicken or mutton are served, and it’s the one day people try not to serve

the same old-same old staple: rice. Many people attend church services and have

parties with friends and families. Even many Muslims join in some of the festive

atmosphere, but not for the same reasons mind you.

Up next: Art and Literature

.JPG)