Mali is rich in visual and textile

arts. Many of these arts are tied to day-to-day living, though. Textile arts

are one of the most common artistic styles easily seen in Mali. Both men and

women wear brightly colored, patterned cloth. They’re known for a type of cloth

style known as mud cloth, which has abstract patterns made from mud. Typically,

this is a woman’s art.

To go along with the art of textile

making, many Malians are adept at making jewelry. Because of Mali’s history,

gold is the preferred metal in jewelry for most of the people; however, the

Tuaregs prefer silver. Styles depend on personal taste and on tribe. Some

tribes have their own particular style, sometimes with patterns that reflect

their history or ancient religious views. Shells, clay, amber, wood, and stone

are also used in making jewelry.

They’re also known for their

woodcarving. Like many other cultures in Western Africa, wooden masks and

sculptures are a part of many Malian cultures. The masks are actually used to

disguise the person wearing the mask when they impersonate ancestors or gods.

Some tribes, like the Dogon, believe that when a person dies, their spirit

stays in the mask, so therefore masks are an important part of funeral rites. The

idea of gender is very important and much of their society is drawn on gender

lines. In their sculptures, body features are often exaggerated to make the

distinction between genders.

Mali has a particular unique type of

architecture, at least different than most other building types in Western and

Northern Africa. Many of the buildings (especially mosques) here are built

using sun-dried mud on top of tree branch beams. Even the shapes of buildings

will vary slightly from other regions as well.

|

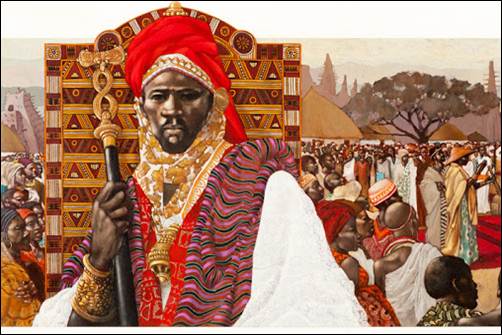

| Askia the Great |

Even as far back as the early 1500s,

historians have noted the importance of literature in Mali. One of the great

military leaders and emperors of the Songhai Empire, known as Askia the Great,

was credited with promoting universities and Malian education at the time. Not

only bringing in some of the world’s greatest scholars, he also built one of

the largest book publishing centers in this region of Africa. One early explorer

wrote about this area, saying that the demand for books is huge, especially

from the North African states, and that Malians earn more profit from producing

books than any other industry.

|

| The djali from Mali (come on, it rhymes) |

Like other areas of Africa, Mali’s

literature is rooted in the traditions of the djali (or sometimes spelled jali, jeli, djeli, or sometimes referred

to as a griot). Djalis were an

integral part of the Mali Empire and had a great responsibility: they are often

quipped as walking history books, but essentially that’s what they were in a

nutshell. But not exactly. Yes, they were great storytellers and musicians who

retell historical stories and family traditions, but they also work in satire,

gossip, political commentary, praise songs, among other topics. One of the most

well-known historians, Amadou Hampâté Bâ, spent a large part of his time

studying these traditions.

Some popular Malian writers include

Yambo Ouologuem (known for his book Le

Devoir de Violence, it was raked with controversy over plagiarism), Maryse

Condé (descended from the Bambara people and writes on their culture, although

she lives in the French Antilles), Massa Makan Diabaté (known for his work The Epic of Sundiata and the Kouta

Trilogy, he’s a descendent of griots), Fily Dabo Sissoko (author and political

leader, writing about the Negritude movement, died in prison), and Moussa

Konaté (teacher, writers, playwright).

Up next: music and dance

No comments:

Post a Comment