Equatorial Guinea shares similar cultural aspects with other

countries that are nearby, so it’s not surprising that they would also share

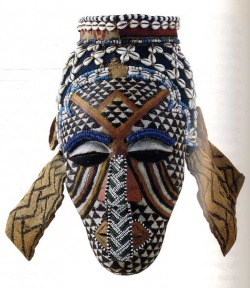

similar arts. Mask-making is one of those arts that pan across much of Western

Africa. Each mask has a different

meaning, although most of the designs depict animals such as crocodiles and

lizards.

Art from the Fang tribe is probably some of the most iconic

art from this area. Their art

tends to be more abstract and conceptual in nature. They also made masks, which come in a variety of styles

(long necks, full figures, half figures), painted in a variety of earth tones. Some

of these masks are used in religious and funeral ceremonies; others are used as

part of rituals in secret societies; there are some that are for hunting; and some

for music and dancing.

Sculpture is also a popular medium among Equatoguinean

artists as well. One artist, Don

Leandro Mbomio Nsue, is probably the most famous artist from this country. Studying initially in the city of Bata,

he later moved to Spain to study further.

He was interested in the styles of Pablo Picasso, whom he later became

friends with. Picasso’s style and

individuality can be seen through Mbomio’s own work, and in fact, he was often

called “the black Picasso” by many artists throughout the world. Mbomio has been nominated and the

recipient of numerous awards and represented Equatorial Guinea through his art

and as an ambassador for peace through UNESCO.

And even though Spanish is the official language of the

country and most people in Equatorial Guinea can speak it and read it, their

canon of literature is scarce. The

Spanish and Portuguese were the first ones to write about this country, but it

was mostly in a travel logs, historical accounts, and often referred to the

people in a second-class sort of way.

The earliest accounts of literature by native Equatoguineans are

narrowed down to two novels written in the early part of the 20th

century. Published journals became

popular, as well as writing down local folklore for preservation.

|

| Juan Balboa Boneke |

After independence there was a general silence. Unlike other African countries where

many anti-colonial works were being published, literature in Equatorial Guinea

remained unknown and unpublished. Even poetry struggled. It certainly had

something to do with the way the government was at the time. Censorship was deep.

Most of the literature that was being produced still seemed to appease the

colonial powers, rather than the independent ones. And once the heavy hand of

the government took a firm grip on the nation, many of the writers and artists

fled the country, heading to Madrid and other areas of Spain.

Some of the most notable names in literature are Raquel

Ilonbé (born in Equatorial Guinea, moved to Spain as a baby, returned as an

adult and is known for her collection of poems called Ceiba and for writing the first children’s book), Juan Balboa

Boneke (famous for his poetry, he tends to mix various words of the Bubi

language in with Spanish; he is also famous as an early political essayist), and

María Nsué Angüe (she was the first woman novelist, publishing Ekomo in 1985; telling the story of a

Bantu woman from the point-of-view of a man to show the patriarchal society of

postcolonial Africa).

While literature from this country is not large, it is

there; however, it's seemingly nonexistent in modern anthologies of Spanish

literature on a whole. And I wonder why this is. I’d hardly think that there

isn’t anything of caliber to include; perhaps it’s just not promoted in the

same fashion as other arts. In the

early 1980s, the Center for Hispanic-Guinea Culture was created, designed to

promote the cultural arts and included its own magazine and a publishing

company. Its goal is to highlight

and showcase talented Equatoguinean writers. It’s too bad that no one funnels more money into this

institute with connections to the local schools to promote young writers to be

heard and published on a global scale.

Up next: music and dance

/2.jpg)