Czechs are renowned for their glass-making art and

their crystal. I’ve been a huge

fan of art glass ever since I saw a Dale Chihuly exhibit when I was in college

(although he studied more of an Italian and French style art glass, I think.). Art glass, made in the original way, is

heated and then mouth-blown using a special tool and then decorated by hand. While

the earliest glass-blowing techniques were developed in Egypt and spread

throughout the Mediterranean, the Syrians invented the glass-blowing tube that

helped to revolutionize this art. Part of the reason why art glass is so popular in central Europe

is because of the natural raw materials, especially in the form of quartz veins

along the Lusatian Mountains. Small pieces of this type of glass have been

found in ruins dating back to medieval days. During the 17th

century, glass artists began developing a type of extremely clear, high-quality

glass called crystal, which is shaped and cut by using special rotating copper

wheels. With the creation and production of crystal chandeliers during the 18th

century, business boomed, but then lagged behind when glassmakers didn’t quite

adhere to growing trends elsewhere. Through different trends and styles of

engraving, inlays, and painting, Czech art glass is still loved and a popular

exhibit in art museums all over the worlds.

One of the most well-known painters is Alphonse

Mucha. His artistic styles gained international notability at the 1900

Exposition Universelle, and his style soon became known as Art Nouveau. A lot

of his art can be seen in postage stamps, banknotes, and ad posters for various

shops and theatres and such. One

of his legacies is a set of large paintings that depict Czech and Slavic

history known as The Slav Epic. It was a series of 20 paintings that he

bestowed upon the city of Prague as a gift to the city he loved. When the Germans entered into

Czechoslovakia, he was among the first to be rounded up and interrogated.

During this long interrogation, he contracted pneumonia, and although he was

released, it took a toll on his lungs.

He eventually died of an infection in his lung during the summer of

1939.

For the most part, Czech literature is written in

Czech. For this reason, Prague native Franz Kafka (who is fluent in Czech) is

not included in the Czech canon of literature since he wrote in the German

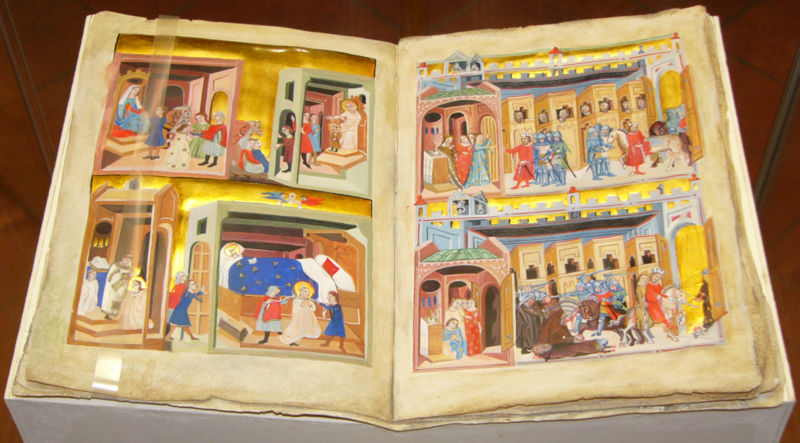

language. The earliest pieces of

Czech literature were mostly liturgical in nature, and mostly written in Old

Church Slavonic using the Glagolitic alphabet (that Saints Cyril and Methodius

developed). Of course Latin was

also widely used in religious matters as well, later changing over to Czech or

German after the Middle Ages. During the Baroque period, Catholic poetry and

prose were pretty much the best-sellers out there. Hagiographies were very

popular during these times as well. (I had to look up hagiography: it’s a

biography written about a saint and the miracles they did.)

The 18th and 19th centuries

were changing times in Czech literature. Classicism became the most noted

genre, especially in the German and Austrian style, and the sciences also began

to be explored. Historical accounts were being documented, and grammars were

being nailed down and standardized. Several writers were also making efforts in

another field: drama (which generally mimicked what the Germans were already

doing). While they were part of

the Austro-Hungarian Empire, emerging authors were exploring new paths, incorporating

philosophical themes and the current hot genres for that time. Among these

authors were Božena

Němcová,

Karel Mácha, and Jan Neruda (the namesake of where Chilean poet Pablo Neruda chose

his pen name).

|

| Jan Neruda |

The 20th

century brought about an array of avant-garde writing with topics delving into

women’s rights, anarchy, expressionism, social commentary, and other literary movements

and liberal topics. Drama, poetry,

and prose all fell into these various movements. During the Communist years, much of this literature turned

to ideals such as freedom and democracy and actually still circulated somewhat

freely. However, as censorship

began to take its ugly hold, most of these authors fled abroad. Their works began

to be read less and less in Czechoslovakia, but gained a different readership

as it was translated into other languages. One of these poets and playwrights

is none other than Václav Havel. I first heard of him on The Last Word with Lawrence O’Donnell a few years ago when Havel

had passed away. He was the last president of Czechoslovakia and the first

president of the Czech Republic. The author of over 20 plays and numerous

non-fiction works, he was ranked fourth in a 2005 poll by Prospect magazine of the world’s top 100 intellectuals. Because he was a dissident during the

Communist years, he was imprisoned, and during those years, he wrote many

letters to his wife Olga. Years later, these letters were compiled in a book

called Letters to Olga,” which I’ve requested from the library. It’s said that

this book is one that author Salmon Rushdie always carries with him, so I can’t

wait until my book comes in.

Up next: music and

dance

No comments:

Post a Comment